The debate as to whether mental disorders are biological diseases or whether they are merely deviations from social norms is not new. Plato takes on this question in the Phaedrus, a dialog dating back to ancient Greece.

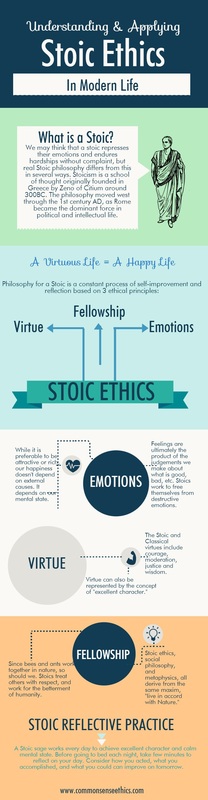

In 2013, C.D. Herrera pointed out that philosophical discourse about mental illness started with the Greeks: “Meaningful talk about inclusion and justice has, since Plato and Aristotle, included observation and speculation which have been directed towards answering questions of what we should do when people reason differently, when they manage emotions differently, and when they resist attempts to bring them into line.”

Socrates made some acknowledgement of the debate over what is actually a mental illness versus what is wrongly categorized as one. He divided madness into two categories: “biological disease,” and behaviors that simply differed from the accepted “conventions of conduct.”

His student, Plato, is more of a mixed bag when it comes to how he viewed and sometimes stigmatized those with mental illness. On one hand, Plato thought that people whose behavior merely deviates from conventions of conduct includes artists, lovers, religious zealots and nonconformists whose behavior derives from what he calls “divine inspiration,” rather than the values of mainstream society.

On the other hand, he seemed to be in favor of keeping those with mental differences away from society. In his dialog Laws, he proposed a system of government formed to eradicate “diseases of the soul.” In his article Ancient Philosophers on Mental Illness, Marke Ahonen notes that these were moral failings, not mental disorders:

“Unlike other citizens, they are not held responsible for the offenses they may commit (cf. 864d), and it is their family members who pay a fine if they fail in their duty to guard them,” the article noted.

One might ask how much things have changed today. Society still finds ways to separate us and keep perceived “others,” in their confined and segregated spaces. To believe that someone is mentally ill or a bad person based only on thoughts and behavior that differ from the norm, (Socrates’ “conventions of conduct”) is still common. And it must be a very lonely way to think about people who reason or manage emotions differently.

You can’t discuss mental health without discussing Freud. In this context, it’s because Freud studied the psychological alienist tradition (1881) yet developed theories and understanding that everyone is neurodiverse based on nature vs. nurture, trauma, repressed childhood experiences, and so on.

It was Freud who said, “The optimum conditions for -psychoanalysis- exist where it is not needed — that is, among the healthy.” He is the first psychologist to understand that trauma is a part of life, and it can lead to addiction, cleaning too much (later known as OCD), and melancholia. It set up the next generation of psychiatry and philosophy to embrace the idea that every single person thinks differently.

However, around 1905, he chooses to veer off into his repressed sex dreams tangents. However, Freud's observations remained the dominating Western theories in psychiatry until the 1960s.

Now, we’ve circled back. The rebellion against the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) has led to questioning disease model psychology. Sure, we no longer used leeches, but we did use a cruel and crude version of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Yes, women's mental health stopped focusing on the hysteria about hysteria, but we still raked Betty Ford over the coals for seeking therapy in the ‘70s.

So, when you hear the word neurodiversity, think of it as an attempt at destigmatization of those with mental health challenges and differences. As Erick Ramirez stated in his article, Philosophy of Mental Illness, “Forms of cognition currently seen as dysfunctional, ill, or disordered are better understood as representing diverse ways of seeing and understanding the space of reasons.”

The ideal would be more inclusion of the neurodiverse in regular society. We stop placing children on the Autism spectrum in low-expectation classes. We remove the stigma of medication and therapy. I continue to see those with ADHD ridiculed and called addicts because we do not take the time to understand the diagnosis or its treatment.

Most of all, we do not criminalize mental illness. It was not so long ago that we institutionalized those who did not think in terms of “norms.” We continue to imprison them whenever possible.

We also do not go the Freud route, either. Dream interpretation and sex therapy don't really work for some groups of people.

Humanity is still working on getting it right. Neurodiversity is about acceptance, equality, and inclusion (unless thoughts turn into violent actions that harm others). Philosophers leave road maps for all aspects of life. It is a timeline of progress, and sometimes not.

~

Sources:

cambridgescholar.com - Ethics and Neurodiversity

journals.sagepub.com - Ancient Philosophers on Mental Illness

frontiersin.org - Psychoanalysis and Neuroscience: The Bridge Between Mind and Brain

Sunshinebehavioralhealth.com - Home page

iep.utm.edu - Philosophy of Mental Illness

Read Next:

4 Life Lessons We Can Learn From the Cynic Philosophers

A Meditation on Courage

Wise Advice on Human Flourishing in 10 Terrific Quotes

Pin This: