This is actually a difficult question – which philosophical texts are best for beginners? But it’s also one that I get asked pretty regularly. I typically suggest starting with Plato, and occasionally delve a bit deeper into the topic, but admittedly haven’t devoted the thought and attention it really deserves to give a proper answer. So when Leah brought it up as a matter that might be addressed, and suggested we record a conversation on her YouTube channel about it – which you can watch here – I thought writing a bit first might help me sort out my thoughts on the topic.

Addressing One Preliminary Concern

All of this is really nonsense. It’s entirely understandable and forgivable, if this is just the would-be-student winding him or herself up. It’s much less so when someone else tells or sells this to others as what must be done. You don’t need to read the books and authors in the “right order”. Unless you’re the sort of person who takes some sort of indelible stain in your brain from what you read – in which case, I am sorry to say, you will not get much from philosophy – you’re not going to damage your mind by reading around the canon at the start, rather than buckling down with some sort of rigidly arranged list.

It is perfectly fine to read Aristotle before reading Plato. It’s equally all right if the first book of philosophy you encountered was Epictetus’ Enchiridion. You’re even all right if you started out with some work by Bertrand Russell, or Ayn Rand, or Hannah Arendt (and if you’re wavering between those, let me suggest you choose the last one).

Here’s why: whatever book you pick, whatever author you start with, you’re probably not going to understand most of what you read the first time you make your way through it. If you come away from an initial reading of Plato or Descartes, and you feel like you solidly grasped everything you read, that feeling is very likely wildly off-base. Often all it takes is a second reading to realize how much you missed the first time around. And different readers are going to come away with different things – usually a mishmash of some rightly understood points and other mistakenly mixed up ideas – when reading the same texts. All that is ok – in fact, it is normal.

Studying philosophical works is an iterative, interpretive, and cumulative process. It’s iterative – you are going to have to read and reread philosophical works, hopefully getting a bit more (even if that is just seeing better how things fit) with each reading. It is interpretative – reading isn’t just a passive transfer of information from the thinker into your head. Whether you realize it or not, you are actively engaging with those thinkers you read and the ideas and arguments they propose to you. It’s cumulative – as you read more and continue your education in philosophy, you start to grasp how various thinkers, movements, topics, and ideas are connected with each other. This in turn provides you with a much more solid understanding of what you are (re)reading.

So if you’re the sort that worries about “getting it right” by reading the right texts and thinkers in the right order, setting down the optimal foundation for all of your further study, there’s good news and bad news. The bad news is that it’s pretty much impossible for you to do that. There is no such perfect foundation, system, or course of study. The good news is that you can study and learn in the field of philosophy just fine without that. And even more good news, if you’re suffering from that anxiety, you can – if you choose to – set it aside.

Primary or Secondary Texts?

Perhaps a good “Introduction to Philosophy” textbook would be a good place to start? They often contain some extracts from texts, along with timelines, biographical blurbs, and a good bit of summarization by the author(s). Best of all, they are (hopefully) designed for first-time students with no background in philosophy. Alternately, a history of philosophy might provide a better introduction to the field, giving a sense of the “big picture”, tracing out the stories of ideas and schools through the ages. Or maybe one of the many books written for popular audiences would work better. There is an entire literature out there designed to cater to those who would like to take their philosophy in little doses, coated with a good bit of sugar or salt. (There’s also another sort of secondary literature that practically nobody who isn’t a professional in the field reads – the sort of books and scholarly articles that focus on particular thinkers, movements, topics, or texts – but other than mentioning that, we needn’t discuss that any further here.)

There’s absolutely nothing wrong with reading secondary literature. In fact, even the fluffiest of philosophy-lite airport kiosk books that more name-drop philosophy than actually discuss it – even that – can become the equivalent of a gateway drug to the harder (and far better) stuff. You can start by reading secondary literature if that’s all you’ve got, or that’s all you feel you’re up to (though you’re likely wrong about that), and you’re not going to ruin your progress towards studying actual philosophy from original texts someday, unless you fall into one of three traps.

The first one, of course, is allowing yourself to get too used to reading texts of that sort, and not start acclimating yourself to the original stuff. Do that too long, and you’re going to find reading primary texts not only more difficult, but also more frustrating. “Why couldn’t Descartes have communicated his ideas as clearly as the person who summarized his works did?” You’ll find yourself asking such questions, and if you don’t see the absurdity in that, well, you’re in for a rough ride.

The second one is to actually believe what the secondary literature says. Even with generally decent histories of philosophy – like for instance that of Friedrich Copleston - you really shouldn’t put too much faith in the story the author is telling. Until you actually read Aristotle or Pascal for yourself – actually until you’ve become quite conversant with their thought, at least on some matters - you really don’t know for sure how much of the tale you’re being sold is fiction. If you don’t follow this rule, you might well end up reading Hegel and being upset with him for not placing everything into the “thesis-antithesis-synthesis” schema some hack told you Hegelian philosophy was all about!

The third trap is to accept over-simplistic categorizations of philosophers from secondary sources. Philosophy is definitely not – despite this being a catchy phrase, and setting aside that Whitehead is otherwise a quite brilliant thinker – anything remotely like a set of footnotes to Plato! There is no basic conflict running down the ages between Platonist idealists and Aristotelian realists, between empiricists and rationalists, between collectivists and libertarians, or whatever other good guys and bad guys (since such narratives inevitably lurch in that direction). Reality is far more complicated than simple schemas like that. And when you realize that philosophers themselves are not only parts of that reality but also trying to make sense of that very reality, that should give you a bit of pause. The same caution goes, by the way, for any neat division of thought into historical periods or movements. The fact that you can call Rousseau a “romantic” does not mean that term really helps you grasp Rousseau’s thought.

I start all of my students off with primary texts. All of them. I’ve used textbooks or histories of philosophy sometimes as supplements, but I always direct students first and foremost to primary texts. I also give them a pep talk about their own capacities to read those works - which tends to be needed for some – and I make sure to provide them with lots of support in the form of lectures, discussions, exercises and examples, handouts, videos, lesson pages, etc. – because many of them also need (or at least benefit from) that as well. But I hammer the point home that, when we are studying philosophy, we are focusing on the thinkers themselves, reading their actual works, discussing ideas drawn directly from their texts, and making them communicate their insights to us in the present.

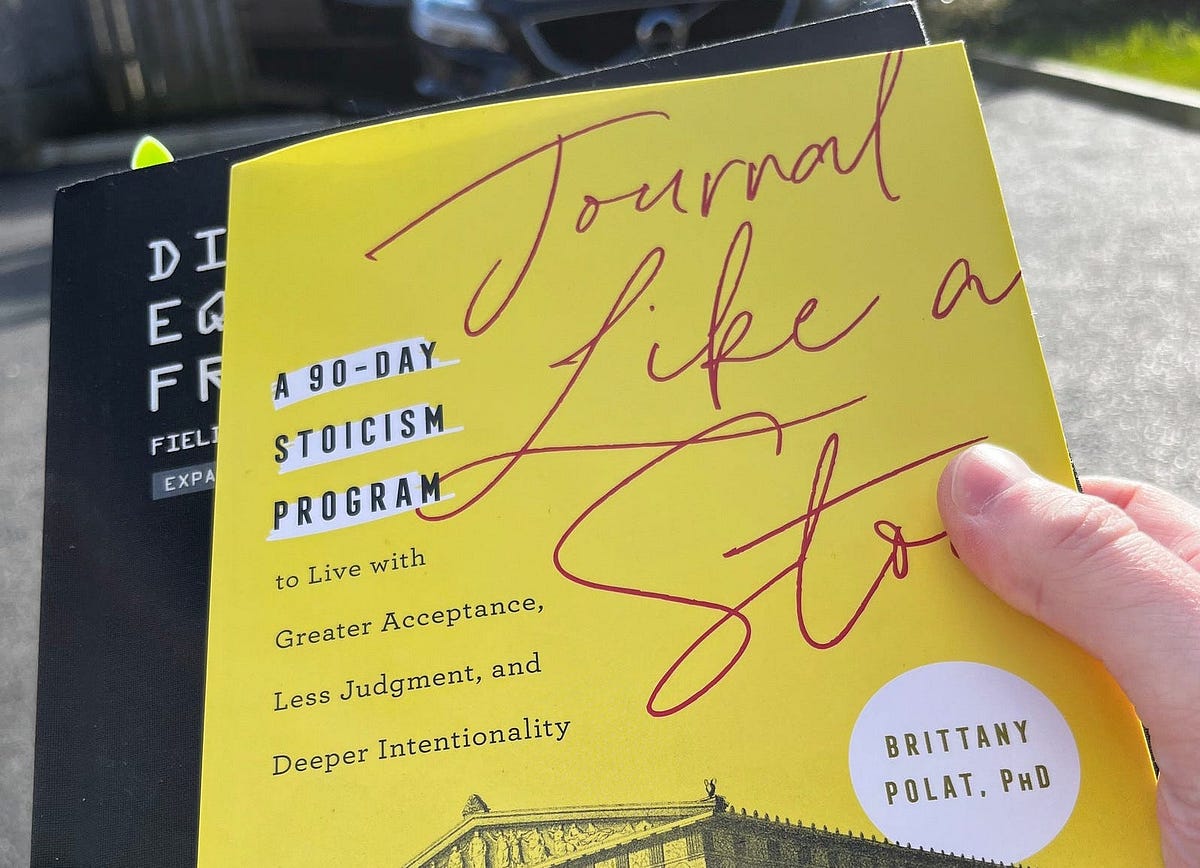

I’ll say one other thing about the importance of sooner or later getting to primary texts – I hope that it is sooner! – and that is this: Reading the works of original thinkers in philosophy not only cuts out intermediaries (however well-intentioned) between you and the author him or herself, so that you discover what Wollstonecraft or Sartre actually did say, not just what someone else has decided to give you by way of excerpts or summary. That by itself is sometimes quite mind-blowing. Reading Epictetus, rather than just reading contemporary Stoic literature about the guy, will open up Stoicism to you like nothing else – just for one example. Reading the real stuff straight also does something else.

It gives you some sense of what philosophy can and does look like. If you were just to read academic journal articles (which unfortunately is what happens at some schools) you could certainly be forgiven for thinking that is what philosophy should look like, the form it should appear in. The same goes for textbooks, or histories, or popular literature. Each of them is a kind of genre, and is restricted by the scope of that format. What are the genres we discover philosophy taking on? Dialogues, treatises, lecture notes, letters, stories, conversations, poetry, disputed questions, meditations, collections of aphorisms, polemics. . . just to name off some commonly encountered forms. Why rob yourself of this richness? Sticking with the secondary literature is a rather sanitized experience like sitting on the couch, playing a video game, rather than actually getting out and walking in, looking at, smelling and touching, the rich and complex world available to you.

10 Books For Beginners to Start With

I decided to keep the list relatively short. Ten is a good number for these sorts of lists. I have also drawn entirely and unapologetically from texts within Western philosophical traditions. It’s not that I don’t think that other traditions – particularly but not solely Chinese and Indian – don’t offer interesting thought well worth engaging. It’s rather that, since I don’t claim any particular expertise in non-Western philosophy, it would be less useful for me to write, and for you to read, what I have to say about it.

There’s one last thing to say before setting out the list. Since we do have available some good volumes that include several works by the same author, I decided to include those under the rubric of “books” here.

Here’s the ten books of that sort that I settled upon:

1. Plato, The Last Days of Socrates – this includes four dialogues: the Euthyphro, the Apology, the Crito, and the Phaedo

2. Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics

3. Epictetus, Discourses, Fragments, Handbook

4. Augustine of Hippo, Confessions

5. Boethius, Consolation of Philosophy

6. Anselm of Canterbury, Three Philosophical Dialogues – this includes On Truth, On Freedom of Choice, and On The Fall of the Devil

7. Thomas Aquinas, Selected Writings – includes a wide selection of Thomas’ works

8. Rene Descartes, Meditations on First Philosophy (with the objections and replies)

9. Mary Wollstonecraft, Vindication of the Rights of Women

10. Friedrich Nietzsche, The Genealogy of Morals

There are an entire host of objections one might make to this list (and feel free to do so in the comments section provided to you here). In fact, were the situation reversed – and I was the reader looking over a similar list you provided – I would likely raise some objections on my own part! At the same time, I’ll stand by this admittedly somewhat idiosyncratic list, and make a case for it.

One kind of criticism that can be made over and over again runs like this: “How could you possibly have left X off of this list? He or she is a philosopher acknowledged almost universally in the profession of being of first importance!” My answers to this would vary, depending on the figure being proposed.

Thomas Hobbes almost made the list – and I would have included Leviathan as the selection – but in class after class (since I do teach Hobbes pretty frequently), I find that the very fact that he writes in 17th century English – and, for someone like me, such interesting language – tends to constitute an impediment for the 21st century reader. Even if you use an edition that regularizes the orthography and punctuation of his prose, Hobbes can be pretty tough going. I find similar issues often arising when teaching John Locke and David Hume as well. All three of them are authors one ought not only to encounter early on in the course of philosophical study, but also to spend time with, and to return to periodically. But in my experience they prove to be unduly difficult starting points for the average person.

A number of other philosophers employ – and sometimes even coin - a considerable amount of technical terminology that also renders them quite difficult for the reader just digging into philosophy for the first time. Immanuel Kant provides a prime example. Many of the terms he use amount to a sort of code whose seeming incomprehensibility initially repels students, but once cracked, yields some very interesting philosophy. Again, Kant is definitely someone worth studying, but perhaps not right at the start (at least not all on one’s own – if you’re struggling with Kant’s Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals, you might find this playlist useful).

It’s desirable that the philosophical texts one reads pique, capture, and hold one’s interest. I don’t assume that will necessarily be the case with each of these ten texts for every single starting-off student, but these do tend to be among the more stimulating works. By contrast, a book that I myself consider quite fascinating – and which I do think one ought to study at some point – Jeremy Bentham’s Introduction to Principles of Morals and Legislation, is quite boring to read for many people. It is a seminal classic of Utilitarian philosophy, but precisely because of his penchant for distinctions, examples, and enumeration, after a while, it can become a bit mind-numbing. What we want for this sort of list is precisely the opposite.

Why These 10 Works?

When people ask where they ought to begin in reading philosophy I always suggest starting with Plato. And given how important his teacher, Socrates, was in Plato’s own philosophical development, why not begin with these dialogues that set out the drama of Socrates’ trial, conviction, imprisonment, and execution? There is also a lot of fascinating philosophical argument going on in these, especially in the Phaedo, and you’ll get introduced to some of Plato’s own key ideas.

Aristotle is a bit more difficult to approach, since what we have are philosophical treatises rather than dialogues. They are fairly systematic, but Aristotle does have tendencies to approach an issue from multiple vantage points, to treat a matter in outline and expect you to fill in some of the blanks, and occasionally to stray from the topic. But he is a brilliant thinker, and his Nicomachean Ethics is probably one of the most immediately accessible of his works for a beginner. Reading it, you’ll not only be introduced to a number of important concepts and distinctions in ethics, but also to views on human nature, social and political organization, and even the range of relationships he calls friendships.

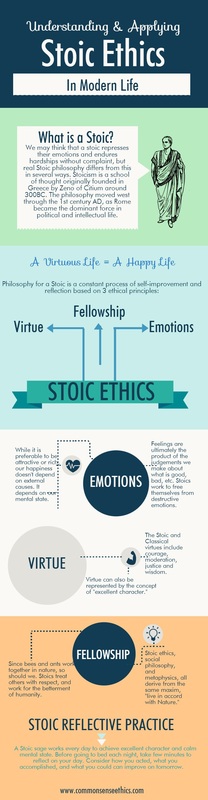

I waver a bit when it comes to who to endorse as the best author for your initial encounter with Stoic philosophy. There are points to argue in favor of Seneca or Marcus Aurelius, but when it comes down to it, my judgement is that Epictetus just is the better choice. You get a lot more to work with, and more systematically organized in Epictetus, than you do with Aurelius. Seneca’s Letters are also an attractive introductory text, but I think the Discourses just offer a more substantial engagement with Stoic thought.

Augustine was a highly prolific author, and a solid philosophical education will inevitably involve you in reading at the very least several other of his works, but the Confessions really is an excellent work to start with. It is at the same time a fascinating autobiography of debauchery and spiritual struggle, and a set of continued philosophical and theological reflections, and it culminates in classic metaphysical meditations on the very nature of time and what creation means.

Given the list so far, the Consolation of Philosophy brings together and reinforces certain threads of the earlier works. Boethius, like Socrates, is unjustly condemned to death and has to come to terms with his fate. He also weaves together elements and arguments from Platonic, Aristotelian, and Stoic philosophy within a broader Christian context without ever mentioning Christianity.

Anselm is better known for his Proslogion (which contains one version of what has come to be called the “ontological argument”) and for his Cur Deus Homo (which contains an innovative and influential account of the atonement and incarnation). But for someone just beginning, I think those three treatises provide a better place to start. They provide very interesting analyses of different modalities of truth, a broad conception of justice, the workings of the will, the motivations rational beings can and should have, and of course some speculation about the fall of the Devil.

Thomas Aquinas was a prolific writer, and among his most important contributions is the massive (and unfinished) Summa Theologiae. That’s definitely not a work I’d suggest one tackle all at once, even if Thomas says it was intended for beginners. But his thought does provide an excellent introduction to – and example of – a Scholastic way of proceeding in philosophy. The volume I recommend here contains a number of good representative selections from that Summa, and a lot of other interesting material.

When encountering Rene Descartes, you could go with his Discourse on Method, but when there’s sufficient time available, I prefer to have students encounter him through his Meditations on First Philosophy. It covers more important topics along the trajectory of the Cartesian project, and goes into more depth on many of them than does the shorter Discourse. Agree or disagree with him, love him or hate him, Descartes is definitely someone worth encountering early in your studies. And though he is grappling with difficult concepts, his writing is quite clear and approachable.

Mary Wollstonecraft is a relatively underappreciated writer, working right at the cusp between the early modern period and the 19th century that she didn’t get to see. She’s rightly viewed as a feminist, since she carried out some cultural analysis still largely relevant today, and made a strong case for equality between women and men. Her Vindication of the Rights of Women is an excellent work within the virtue ethics traditions, and remains quite accessible to the contemporary reader.

Friedrich Nietzsche, like everyone else on the list, can be somewhat difficult reading, if the goal is to fully understand his books. But, there is quite a lot that a first time reader can get out of his works as well. He is definitely not a systematic thinker, in fact, at times deliberately anti-systematic. But his Genealogy of Morals is probably the most systematic of his works (The Birth of Tragedy arguably is as well, but I’d say it requires more background in ancient literature), and so that’s my selection for rounding out this rather short but hopefully helpful list.

~

You May Also Like:

6 Tips For Teaching Yourself Philosophy

Are You a Disordered Philosopher?

9 Great Critical Thinking Books for Children and Teens