One important meta-ethical distinction concerns the split between ethical subjectivism and ethical objectivism. Moral subjectivists claim that there are no moral truths, and that moral propositions cannot be true or false. Ethical objectivists think that there are objective moral truths.

It is my contention that the meta-ethical subjectivism/objectivism dichotomy can be reconciled. While the two may seem incompatible on the surface, there is no fundamental incompatibility between these distinctions, only differences based on perspective. Subjectivism and objectivism are actually complementary to one another.

I concede that ethical objectivism and ethical subjectivism are prima facie incompatible. Some level of meta-ethical subjectivism is inevitable because of limited facts, knowledge and perspective at the individual level. Moral truth is somewhat subjective for each person because of imperfect, atomistic knowledge. But subjectivism at the individual level does not preclude the existence of moral truth external to us at the objective, eternal level. Just because we are not aware, or not fully aware of objective moral truth, does not mean that objective truth does not exist externally.

Truth cannot be fully known without all relevant facts. Absolute, objective truth is based on omniscience; being in possession of all the facts, and combining perfect rational, intuitive and eternal knowledge. Relative truth is subjective, based on imperfect knowledge, and on the facts available to us, not all extant facts.

What is Objectivism? What is Subjectivism?

To illustrate my argument, let me invoke an ancient parable. Three blind men come upon an elephant. Being blind, they have never seen one before, though they may have heard of the objective concept of an elephant. In other words, their knowledge of elephants is limited.

The men begin to feel parts of the elephant’s body in an effort to learn more about it. They touch its legs, its trunk, and its tusks. When the men describe what they each feel, the first man describes a thick tree trunk (the elephant’s leg), the second man describes a narrow, slender tree branch (its trunk), and the third man describes a hard pointy stake (its tusk). The elephant does have legs, a trunk, and tusks. These are the facts.

There is objective truth; the facts about the elephant’s body, and then there are subjective perspectives; the way each person sees the facts. None of the men are wrong in their description of the facts, but they are nonetheless limited by their perspective when describing different parts of the same whole, objective elephant. Their personal experience is subjective because they lack complete knowledge of the entire elephant as it exists objectively.

The blind men are trying to define the objective whole by way of the subjective part, which is the essence of ethical subjectivism. The idea that moral judgments must be either objective or subjective, and not both simultaneously, needs to be explored further. It seems that there is intellectual value in opposing perspectives and not in unity.

How Can We Know About Moral Truth?

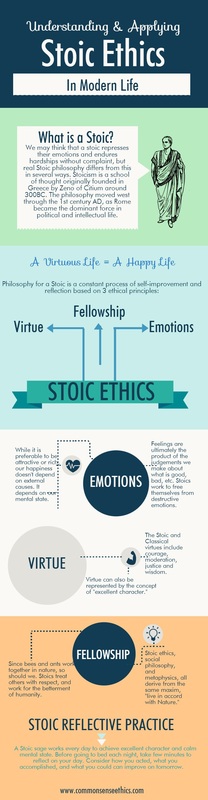

The Stoics generally agreed that knowledge could be obtained through reason, and that we can discern truth from falsehood, but that in practice our estimations can fall short of absolute objective knowledge. Knowledge can be obtained by a sage through the use of reason and discussion with one's peers. The Stoic concept of knowledge is generally consistent with what we know as intellectual knowledge.

Plato's theory of knowledge on the other hand, is more consistent with what we generally know as intuition. In the Republic, Plato writes that we have knowledge of all things innately at birth, but we don't “remember,” our preexisting knowledge until we we make various discoveries that lead to recognition. If all our of knowledge comes without reference to the eternal forms, then we will fail in our quest for knowledge.

We may not have perfect knowledge of objective moral truths, but our not being fully aware of these truths (subjectivism) does not preclude the possibility of their existence outside of us (objectivism). Therefore, I reject the idea that moral judgments cannot be objectively true; it’s our individual knowledge of morality that is subjective, but that does not affect eternal or objective truth. Moral truths are subjective for us, but eternally objective. We should strive for more objective knowledge by uniting our intuition and our intellect.

~

I hope you enjoyed this post! Please also see my essay on normative ethics and natural rights.