I’ve never really thought of myself as a materialistic person. I’ve always worn inexpensive clothes, lived in modest dwellings, and tried to judge my companions by the quality of their character rather than the expensiveness of their possessions.

But when I had kids, my relationship with material goods suddenly changed. My husband and I found ourselves spending a lot of money on nursery furniture, baby gear, and diapers. Then we traded the old, small car for a new, reliable family car. We moved out of our small condo to a bigger house with a bigger yard near better schools. Without really stopping to think about it, we’ve always assumed we have to give our kids as much as we can afford, whether that means high-quality child care or dance lessons or memorable family vacations.

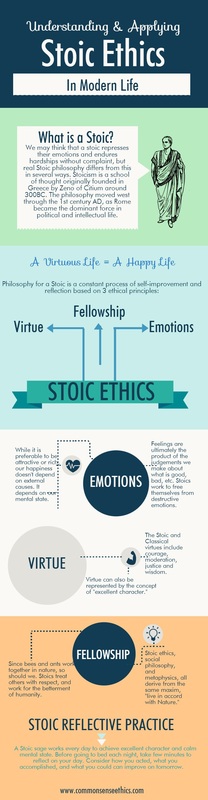

But one thing I’ve learned from Stoicism is that you should never blindly do things without stopping to think about them; you shouldn’t do something just because it seems right, or just because that’s what everyone else is doing.

What if the same thing applies to material goods and opportunities? It seems only natural to do as much as we can for our kids and give them as much as we can. But it’s possible that, after careful examination, we find that giving our children more and better things does not make us better parents. So in this case we need to scrutinize our underlying assumptions about what seems natural.

Let’s start with the basic Stoic understanding of materialism: external goods are preferred indifferents which may be used for good or bad purposes but are not good and bad in themselves. Epictetus says:

“What are externals, then? Material for our choice, which attains its own good or ill through the way in which it deals with them” (Discourses, I.29, 2).

In other words, a wise person can use money and power to accomplish good in the world. If you, as a Stoic, happen to get a lot of money, or power, or other preferred indifferents, then that’s great, as long as you don’t get attached to them. (You have to be willing to let them go with no problem.) But basically, as a Stoic parent, there is nothing wrong with using the external goods you have to live well and raise your children well.

So if it’s fine for us to have and use external things, then what and how much should we give our children? For those of us living in 21st-century developed societies, the question goes far beyond meeting our children’s basic physical needs. Many of us are fortunate enough to have plenty of food, more than adequate shelter, a safe environment, access to many public services, and even disposable income to buy extra things. In this case, what is the appropriate use of externals to guide our children toward eudaimonia? Should we buy more toys? Should we pay for math tutoring? Should we take them to Disney World?

As with so many things in life, I think we must consider externals on a case-by-case basis, trying to look objectively at the components and overall impact of each item. For example, many families buy their children lots of toys. Is there a good reason for doing this? Well, it does keep the kids occupied for a while, and some toys are great for physical and cognitive development. Are there any downsides? Yes, they take up a lot of space, can break easily, and often make a mess. Considering the advantages and disadvantages, it seems reasonable to adopt this practice in moderation.

Maybe we don’t buy as many toys as some other people, or maybe we just limit the toys to a certain beneficial type. Ok, next example: many families sign their kids up for music lessons. Is there a good reason for doing this? Yes, the child learns how to play a musical instrument, which can provide pleasure for the rest of her life, and she also develops hand-eye coordination, persistence, and many other abilities. This seems like a good one. Any downsides? Yes, you have to pay for the lessons and make your child practice (assuming that she doesn’t automatically love it!).

On the flip side, we could instead ask ourselves if there are any harmful effects if we don’t buy lots of toys and sign our kids up for piano lessons. If we don’t pay for piano lessons and soccer practice, will our kids not have the skills to succeed in life? No, that’s not true–they can learn the same skills in other ways. If we don’t go to Disney World, our kids won’t have any wonderful childhood memories? That’s not true either–they can make great memories of us all cooking a spaghetti dinner together.

If we don’t buy them a cell phone in middle school they won’t have any friends, and if we don’t pay for a great college, they won’t have a good career? No, neither of those assumptions is true at all. We can instead teach them not to depend on other people’s opinions of them and to work their way to a career through other means.

My conclusion from all this is that we can and should give our kids external things if we keep the following criteria in mind:

1. We Never Reflexively Give or Do Something Just Because it Seems Like Everybody Else is Doing It

2. We Give External Goods of the Appropriate Quality and Quantity

3. We Never Feel Guilty About Not Being Able to Afford Certain Things

4. We Teach Our Children the Proper Value of Externals

So we’ve decided on a well-considered and moderate approach to externals, even though we know none of these things in themselves lead to happiness for ourselves or our children. Nevertheless, there is still value in teaching our children to fit into today’s society. As Seneca says:

“Let everything in our hearts be different, but let our appearance suit our fellow men…Our life should be a compromise between virtuous behavior and public practice: let everyone admire our life, but also see it as familiar” (Letter 2).

We don’t want to act as if we’re better than everyone else, or go to extremes to prove that we don’t need material goods. It’s all about using our practical wisdom to find the right balance. Fortunately, adopting a Stoic perspective on materialism allows us to function well in society while also teaching our children that material goods are not what really matters in life. This is the true inheritance we pass on to our children, which will enable them to live a good, happy, productive life.

~

You May Also Like:

5 Things That You Owe Your Child

Musonius Rufus' Nurturing Stoic Family or Plato's Gaurdian Automations?

Why It is Wrong To Spank Children - Number 4 May Shock You